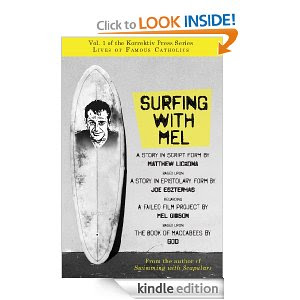

Many of you know Matthew Lickona--from writing Swimming with Scapulars, numerous short stories, the blog Godsbody and its collaborative morph into Korrektiv ("Bad Catholics, blogging at a time near the end of the world"). The Korrektiv Press' second title is Lickona's own Surfing With Mel (Lives of Famous Catholics), a fictionalized version of real life events that reputedly occurred as two Catholic-influenced movie makers--Mel Gibson and Joe Eszterhas--try to collaborate on putting the Book of Maccabees on screen. The narrative in script form (and the real life backstory) is a bit like watching a grippingly written trainwreck in slow motion, but it isn't presented for prurient sightseeing. Between the swearing, slurs, creepiness, humor, and sadness, there are multiple moral narratives here: how do we make moral decisions when we are spinning out of control? When do you give people a chance when they appear to have the moral maturity of a rabid dog? How do you follow God in such an insanely messed up universe, messed up primarily from your own decisions? No easy answers, but it makes for fascinating reading. I encourage people who can handle the language (OK, I've warned you, Mel is not a G rated character): do buy it and read it.

I shamelessly asked Matthew Lickona to talk a bit about the book.

ML: Like

all great and terrible artistic projects, it started with a blog post.

Or, to be precise, with a comment on a blog post. Back in April, I made

note of Eszterhas' leaked letter to Mel, and an old college buddy of

mine chimed in, "Joe and Mel work on an Old Testament movie…THAT'S your

movie, right there. Sort of like The Odd Couple meets The Player." That

was all I needed, especially since Eszterhas' letter reads almost like a

movie treatment. I wrote the opening scene that day.

I shamelessly asked Matthew Lickona to talk a bit about the book.

IC: How did this writing project come about?

IC: Just to be clear for those of us who flunk pop culture exams, how much of this is reportedly true and what comes out of your imagination?

ML: Aw, c'mon - did anyone ask F. Scott Fitzgerald how much of Tender is the Night was

really the story of Gerald and Sarah Murphy? Wait, don't answer that.

Because your answer is probably going remind me that I am not F. Scott

Fitzgerald, and I get all sad when people do that. So, an answer of

sorts: Eszterhas's letter (available online if anyone is curious) was a

laundry list of largely unconnected and seemingly random events: Gibson

ranting about Jews, Gibson ranting about Vatican II, Gibson ranting

about his girlfriend, etc. My goal was to provide connective tissue

between those events - to give them context, and maybe even meaning. So

for example, Eszterhas relates a scene in which an enraged Mel knocks

over a totem pole and screaming at God. I just put moments like that to

fictional use.

IC: You have the character Mel introducing the whole tableau by stating the Church is rehab, and that eventually everyone in the recovery business realizes that there are some who are just not going to make it. It seems like that sets the tone for the whole piece: you introduce a man who is not without his charm and self-awareness, but his demons overwhelm him almost in spite of himself. I came away from this feeling sorrow for the character, but also real disgust. Is that appropriate?

IC: I think you need to explain the "series" proposed on the book cover. What makes a "Great Catholic" here?

IC: I'm a cinema idiot. My viewing tends to be the latest blockbuster Pixar movie because, well, I have lots of kids and little viewing time. So take this comparison with a grain of salt: Being John Malkovich. Similar or not?

IC: This is page-turning reading, and I assume would be intense viewing as well.

IC: This is not really about movie making or the Hollywood beat--it's about two religious and sinful men trying to do the right thing: one who doesn't know what that is, and another who perhaps does, but cannot do it. It's not exactly Everyman, but...have you thought of this as a morality play?

ML: I'm probably not smart

enough to answer that, but I don't know if I would call it a morality

play. I think it's maybe too psychological for that - there's too much

about the way faith is informed by character, for instance.

IC: I have to admit--the women in this script are the most morally clear-sighted. Comment, or not touching that with a ten foot pole?

ML: Well,

I was working from life to some extent. In his letter, Eszterhas often

refers to his wife Naomi's response when he wants to confirm the

outrageousness of this or that action on Gibson's part. She comes off as

Eszterhas' partner, yes, but also as a kind of moral Geiger counter.

"You frightened my wife." "You made my wife cry." You have these artist

types butting up against each other, and she's got the closest ringside

seat. It made sense to make her the moral entry point for the reader,

the one who asks, "Why can't you just walk away from the madness?"

IC: What was hardest to write in this project?

ML: Unfortunately,

none of it was too terribly hard. You have a frustrated Catholic

artist, a guy with anger issues who's struggling with faith, home-brew

theology, a loving spouse… I pretty much just walked into the funhouse

and wrote what I saw in the mirror.

***

My thanks to the author and go and buy it (the ebook is 99 cents). Take your mind off the election.

1 comment:

I think "postmodern morality play" would work, FYI.

Post a Comment